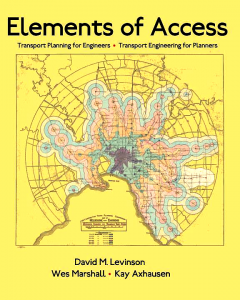

Elements of Access:

Transport Planning for Engineers, Transport Engineering for Planners

By David M. Levinson, Wes Marshall, Kay Axhausen*

336 pages, 164 color images. Published by the Network Design Lab, 2017

ISBN: Softcover: 9781389067617 | Hardcover: 9781389067402

PDF (Electronic Download) (on Gumroad)… $8.88

High Quality Color Trade Paperback (on Blurb)… $28.88

High Quality Color Trade Paperback (on Amazon)… $42.88

Very High Quality Color Hardcover (on Blurb) … $88.88

Order links: transportist.org

Nothing in cities makes sense except in the light of accessibility

Nothing in cities makes sense except in the light of accessibility

Transport cannot be understood without reference to the location of activities (land use), and vice versa. To understand one requires understanding the other. However, for a variety of historical reasons, transport and land use are quite divorced in practice. Typical transport engineers only touch land use planning courses once at most, and only then if they attend graduate school. Land use planners understand transport the way everyone does, from the perspective of the traveler, not of the system, and are seldom exposed to transport aside from, at best, a lone course in graduate school. This text aims to bridge the chasm, helping engineers understand the elements of access that are associated not only with traffic, but also with human behavior and activity location, and helping planners understand the technology underlying transport engineering, the processes, equations, and logic that make up the transport half of the accessibility measure. It aims to help both communicate accessibility to the public.

I Introduction

1 Elemental Accessibility

1.1 Isochrone

1.2 Rings of Opportunity

1.3 Metropolitan Average Accessibility

II The People

2 Modeling People

2.1 Stages, Trips, Journeys, and Tours

2.2 The Daily Schedule

2.3 Coordination

2.4 Diurnal Curve

2.5 Travel Time

2.6 Travel Time Distribution

2.7 Social Interactions

2.8 Activity Space

2.9 Space-time Prism

2.10 Choice

2.11 Principle of Least Effort

2.12 Capability

2.13 Observation Paradox

2.14 Capacity is Relative

2.15 Time Perception

2.16 Time, Space, & Happiness

2.17 Risk Compensation

III The Places

3 The Transect

3.1 Residential Density

3.2 Urban Population Densities

3.3 Pedestrian City

3.4 Neighborhood Unit

3.5 Bicycle City

3.6 Bicycle Networks

3.7 Transit City

3.8 Walkshed

3.9 Automobile City

4 Markets and Networks

4.1 Serendipity and Interaction

4.2 The Value of Interaction

4.3 Firm-Firm Interactions

4.4 Labor Markets and Labor Networks

4.5 Wasteful Commute

4.6 Job/Worker Balance

4.7 Spatial Mismatch

IV The Plexus

5 Queueing

5.1 Deterministic Queues

5.2 Stochastic Queues

5.3 Platooning

5.4 Incidents

5.5 Just-in-time

6 Traffic

6.1 Flow

6.2 Flow Maps

6.3 Flux

6.4 Traffic Density

6.5 Level of Service

6.6 Speed

6.7 Shockwaves

6.8 Ramp Metering

6.9 Highway Capacity

6.10 High-Occupancy

6.11 Snow Business

6.12 Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram

6.13 Metropolitan Fundamental Diagram

7 Streets and Highways

7.1 Highways

7.2 Boulevards

7.3 Street Furniture

7.4 Signs, Signals, and Markings

7.5 Junctions

7.6 Conflicts

7.7 Conflict Points

7.8 Roundabouts

7.9 Complete Streets

7.10 Dedicated Spaces

7.11 Shared Space

7.12 Spontaneous Priority

7.13 Directionality

7.14 Lanes

7.15 Vertical Separations

7.16 Parking Capacity

8 Modalities

8.1 Mode Shares

8.2 First and Last Mile

8.3 Park-and-Ride

8.4 Line-haul

8.5 Timetables

8.6 Bus Bunching

8.7 Fares

8.8 Transit Capacity

8.9 Modal Magnitudes

9 Routing

9.1 Conservation

9.2 Equilibrium

9.3 Reliability

9.4 Price of Anarchy

9.5 The Braess Paradox

9.6 Rationing

9.7 Pricing

10 Network Topology

10.1 Graph

10.2 Hierarchy

10.3 Degree

10.4 Betweenness

10.5 Clustering

10.6 Meshedness

10.7 Treeness

10.8 Resilience

10.9 Circuity

11 Geometries

11.1 Grid

11.2 BlockSizes

11.3 Hex

11.4 Ring-Radial

V The Production

12 Supply and Demand

12.1 Induced Demand

12.2 Induced Supply & Value Capture

12.3 Cost Perception

12.4 Externalities

12.5 Lifecycle Costing

12.6 Affordability

13 Synergies

13.1 Economies of Scale

13.2 Containerization

13.3 Economies of Scope

13.4 Network Economies

13.5 Intertechnology Effects

13.6 Economies of Agglomeration

13.7 Economies of Amenity

VI The Progress

14 Lifecycle Dynamics

14.1 Technology Substitutes for Proximity

14.2 Conurbation

14.3 Megaregions

14.4 Path Dependence

14.5 Urban Scaffolding

14.6 Modularity

14.7 Network Origami

14.8 Volatility Begets Stability

15 Our Autonomous Future

Bibliography

* David M. Levinson is a Professor at the University of Sidney; Wes Marshall is a Professor at the University of Colorado, Denver; Kay Axhausen is a Professor at ETH Zürich